This contribution summarizes the results of the article awarded the Award for the best article in health economics published in 2022, awarded by the Health Economics Association in 2022 and published in Health economics.

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic has profoundly altered our lives. Beyond the devastating death tolls from the virus and the economic collapse, there is a vital dimension that deserves our attention: the impact it has had on our mental health. During the early stages of the pandemic in 2020, several studies showed a worrying deterioration in mental health in the population. Those who suffered the most serious consequences of this mental health crisis were, for the most part, women, young people, caregivers and those who experienced financial difficulties.

However, the causes behind this deterioration have been a matter of debate. A possible explanation is that, in the context of a pandemic, mental health deteriorates due to the fear and anxiety about one’s own health and well-being. An alternative hypothesis is that it is not the pandemic itself, but policy responses, and specifically severe mobility restrictions, that trigger worsening mental health. Both may have played a role in this situation.

Early research on this topic encountered a significant challenge. It was difficult to discern between these two explanations because the pandemic and the containment measures occurred at the same time. That is, the regions that implemented the strictest lockdown restrictions were the same ones that were experiencing a higher incidence of the pandemic. This circumstance made it difficult to identify a control group to determine the causal effect of confinement on the mental health of the population. The first studies showed that, through Google data analysislockdown policies in European countries and US states led to an increase in searches for terms related to loneliness, worry, and sadness. another studyExamining helpline call data in four German states, it found that calls increased more in states where stricter measures were implemented.

The Quasi-Natural Experiment: England vs. Scotland

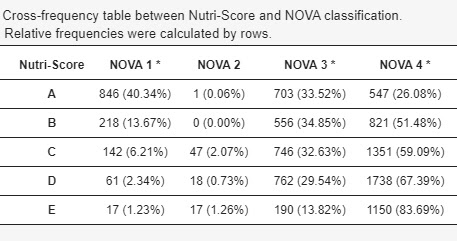

In a joint study with David Stuckler, Alexander Kentikelanis and David Mckee, we took the opportunity provided by the different lockdown policies applied in England and Scotland to evaluate their impact on the mental health of the population. Both countries initially adopted similar containment measures, but starting in May 2020 they began to diverge in their approach. England lifted its Stay at Home order on May 13, while Scotland maintained it until May 29. Importantly, he made this decision even though COVID-19 pandemic trends were similar at the time. In figure 1, these differences can be seen through the «Oxford Stringency Index», which measures the severity of confinement policies.

Figure 1- Evolution of the severity of confinement policies in England and Scotland.

To investigate the impact of these different policy responses, we use “difference in differences” (DiD). Basically, this method helps identify the effects of a policy (lockdown) by comparing the results before and after the change (lifting of lockdown in England), taking into account the differences between the study groups. In this context, we considered England, which lifted lockdown earlier, as our “treatment” group, while Scotland, which maintained lockdown, acted as our “control” group.

We use data from the UK Longitudinal Household Survey (UKHLS), a representative longitudinal sample of the UK population with multiple waves before and after lockdown. To measure the mental health of the population we use the General health questionnaire (GHQ-12), an instrument that has been used extensively throughout the scientific literature.

Main results

As shown in Figure 2a, mental health deteriorated to a similar magnitude in both nations after the start of the pandemic and with strict lockdown (“Stay at Home”) across the UK. However, in late May, in the second round of COVID-19 surveys, mental health began to improve in England following the lifting of the full lockdown order. On the other hand, in Scotland, the situation continued to deteriorate and did not begin to improve until June when restrictions began to be eased. From that point on, the mental health index in Scotland began to converge with that of England.

Results from the DiD method showed that the easing of restrictions in England in the middle of the year led to an improvement in mental health, reflected in a 0.31 point reduction in the GHQ mental health index. This amounted to a 31% decrease from the first increase seen at the start of the pandemic.

Furthermore, our findings indicate that the effects of lockdown were not uniform across all segments of the population. The improvement in mental health following the lifting of lockdown in England was especially notable in individuals with lower socioeconomic status, such as those with lower educational attainment or financial difficulties. By contrast, in Scotland, where restrictions were in place for longer, people with lower socioeconomic status experienced a more pronounced decline in their mental health, while people with higher socioeconomic status appeared to adapt better to lockdown.

Figure 2- Results of the effect of confinement policies on mental health

Conclusions and implications for future? pandemics

Our results suggest that confinement policies significantly affect the mental health of populations. Specifically, our analysis shows that the lifting of strict lockdown in England improved mental health among the population, after a large deterioration observed after the start of the pandemic. Our results suggest that mental health was more sensitive to the imposition of containment policies than to the evolution of the pandemic itself.

The results are particularly relevant when we consider that when England ended the Stay at Home order, many restrictions remained in place. Compared to Scotland, socializing in public places was allowed, but only with one person not from the same household. Bars, retail stores, theatres, gyms and all leisure facilities remained closed. Therefore, our results indicate that lifting the strict confinement while maintaining relatively strong containment can significantly alleviate the mental health burden of the population measured in a short period of time.

On the other hand, our results reveal that people with lower socioeconomic status experienced a more pronounced deterioration in their mental health with the extension of strict lockdown in Scotland. This suggests that prolonged lockdown policies could exacerbate pre-existing socioeconomic inequalities in mental health.

However, it is crucial to note that these results should not be interpreted as support for removing restrictions without regard to public health and safety. If COVID-19 cases and deaths had risen to very high levels after restrictions were lifted, mental health recovery may not have been sustained.

In conclusion, our study provides valuable insights into the complex relationship between pandemic containment policies and mental health. It underlines the importance of finding a balance between protecting public health and addressing mental health challenges arising from necessary restrictions.

In future crises, policymakers must consider the mental well-being of their populations. While restrictions may be necessary to control a pandemic, measures aimed at mitigating the impact on mental health, especially for those facing economic disadvantage, must be an integral part of the response.

.png/4b5cdbc8-a8ee-d344-b4db-f8485338da1f?version=1.0&t=1753686856136&imagePreview=1)

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!